The Kali Gandaki River valley is the deepest gorge on earth if measured from the tops of Mounts Dhaulagiri and Annapurna—which they do. It’s a long way down to the river from the summits of those peaks, both among the top ten highest on earth. Their snow-capped upper reaches are so white and billowy they look more like clouds than mountains. Far below the river runs grey/black from all the clay sediment it carries. I recall the pale waters of the Khumbu district below Mt Everest. The river there is named Dhud Khosi, or “Milk River.” The Kali Gandaki is named after the Hindu goddess Kali and looks more like chocolate milk.

Each Hindu god has a female counterpart—his shakti or consort—who activates his spiritual power and influence. It is the shakti’s female aspect that undergirds the active force; without her, the male deities would be powerless. Kali is one of the shaktis of the Hindu god Shiva, the god of destruction. She is the scary one, with gritted teeth and skulls hanging around her neck. Her skin is dark, like the local waters, so the name of the river stuck.

The arid region of Mustang (Muh-stang) is the most sparsely populated part of Nepal. Small villages dot the riverbank and nestle in the green clefts of side canyons. The stone houses cling to steep ledges below vertical palisades shaped like organ pipes. The towering rock walls are pockmarked with man-made “sky caves” in locations that appear inaccessible to any creature without wings, accentuating the mystery of their origin. Apple orchards and the ruins of watchtowers from the old kingdom are scattered throughout the valley. A few nomads still wander around, though that way of life is slowly fading away. Shepherds herd changra goats that are the source of cashmere wool.

Mustang is north of the Himalaya Range so is always in its rain shadow. The arid, treeless landscape is as barren as the moon. Agriculture would not be possible without an intricate system of irrigation, and even with that consists mostly of high altitude grains like barley and buckwheat, potatoes, mustard, and peas. The soil is fertile and with a little water, apple trees thrive and apple pie is a specialty.

The air is thin and the withering climate is harsh enough to age you in dog years. A stampeding north wind from the Tibetan plateau is funneled between the parallel mountain ranges and stoked into speeds that merit a hurricane rating. They whip up dust storms that could pass for a scene from Lawrence of Arabia. The earthen houses have brightly colored doors but small windows, and no one leaves their shelter without some type of face cover and hat. As the sun rises and the cool night air quickens, the gusts grow ever stronger and more unforgiving, so even on a cloudless day, all takeoffs and landings at the small airport in Jomsom are halted after 10 AM.

The vermillion cliffs are a crash course in geology, their diagonal striations a testament to the tectonic uplift of what was once the floor of a prehistoric sea. Further evidence are the ammonite fossils of sea creatures—known locally as shaligrams—that are found only here and gathered by people of the valley to be sold to tourists and collectors in Kathmandu and abroad. Kali Gandaki is one of the major tributaries of the Ganges, Hinduism’s most sacred river and the “embodiment of all holy waters,” so the shaligrams are revered as a non living manifestation of Vishnu, another god of the Hindu trinity. They are good fortune to those who find one and a talisman to be carried or passed on.

Nepal’s Mustang District, once the Kingdom of Lo, is remote and inaccessible, one of the last unspoiled places on earth. Before 2008 it was an independent kingdom- the “Forbidden Kingdom.” Mustang is sealed off by geography—bordered in the north by the Tibetan plateau and sheltered on both sides by some of the world’s tallest mountains. Strict regulations kept it officially closed to foreign travelers until 1992, and few people even tried to go there before then. It took a month in 1990 for our friend and guide Sanjeev Chhetri to walk to Lo Montong, the capital city, from Pokhara in western Nepal. He slept on the roof of one of the monasteries and then walked back (Sanjeev and his wife Sirish went back to be married there, in full Tibetan regalia). Even now there is a strict limit on the number of visitors, and until five years ago, the only way to get to the capital city, Lo Manthang, was still to walk or go by horseback. Staying independent and forbidden is easier if the outside world can’t easily reach you.

Mustang still harkens back to an old Nepal, like Tibet before it was overrun by Han Chinese. The Dali Lama observed that “authentic Tibetan culture now survives only in exile,” and this is one of those places. It is said that Mustang is more Tibetan than Tibet.

To reach Lo Montong, we flew on a small propeller plane from Pokhara to Mustang’s southern entry point, the town of Jomsom, and from there we traveled north. The drive through Mustang alone could serve as a history lesson—how things used to be before there was concrete or bulldozers. The distance is only fifty kilometers over roads that in places were, as Caroline put it, “beyond horrible.”

We are accustomed to epic road trips in Nepal and had just endured one on our way to Pokhara from Kathmandu when our flight was cancelled due to weather and Sanjeev managed to find a driver instead.

The Kathmandu Valley is as pretty as a postcard, but driving through it requires perseverance and resolve—“more off-road than on,” according to Caroline. It was bumpy, like riding in a tumble dryer instead of an SUV. Rickety bridges spanned rivers swollen from monsoon rains; the only guard rail some bamboo sticks linked together by strings. Caroline again, “No inspections here; they know it’s time for a new bridge when the old one falls into the river.”

This was the main connection between Nepal’s two most visited cities, but the government has stubbornly refused to make road repairs. If we asked our friends why, they answered with the ubiquitous South Asian head bob.

In Nepal, the head bob can mean whatever you want it to mean—a gesture that is neutral enough to allow you to respond without committing yourself. It is like a shoulder shrug and is used to signal understanding, agreement, or mutual bewilderment. Everyone does it, and it is useful enough that I would adopt it for myself if I thought anyone at home would understand it.

The one -hundred-mile journey from Kathmandu to Pokhara took ten hours, and we arrived late at night when everyone else in western Nepal was asleep. By the time we finally pulled into Pokhara, Caroline had escape plans running through her head and was checking flight schedules out of there.

The next morning she told me she was staying, but what really bugged her was not that she had to hold on while being tossed around in the back seat; it was that I had fallen asleep.

Caroline is typically a good sport about our escapades. Before we were married, I suggested that we climb the Grand Teton in Wyoming together and she agreed without really knowing what she was getting herself into. We did it, and sometime later one of our friends remarked, “And she married you anyway?” Eventually, she learned to say no. One time we were in Paris and I wanted us to take a nighttime walk together in a cold rain because it would be romantic. She responded, “It’s just the idea of doing those things that is romantic.”

The people of Lo, known as the Lopa, are closely related to the people of western Tibet, and Mustang was for many centuries a crossroads between India and China. Yak caravans regularly passed through the valley carrying wool, grain, spices, textiles, and handicrafts. During the salt trade, the region was affluent. Some of the monasteries built in that golden age were palatial, although most have succumbed to time and neglect. What remains of the architecture and artwork attests to the opulence of a bygone era.

In 1950 the border was sealed by Maoist China and all trade stopped. The economy now amounts to subsistence farming, animal husbandry, catering to religious pilgrims, and a trickle of tourism.

The sky caves are relics of a time before recorded history. How they came to be is as mysterious as the reasons why. Little is known about their origin or inhabitants, and that they would be inhabited at all is difficult to fathom. Why make what is already a hard place to live even harder? The caves were chiseled into towering escarpments of stone in places that would be fit for a swallow to nest. For a human they appeared very inconvenient, and I wondered how it would feel to live there and climb back to my cave only to find that I had forgotten something from down below.

Artifacts and iconography in the caves attest to a story of sacred worship and burial. A few cave monasteries still have a solitary monk living in them, meditating and doing other things that monks do. Candles abound and need to stay lit, and there is a large store of sacred texts to study and preserve.

The sky cave’s origins have traditionally been explained as mysterious places for ritual and ceremony, where robe-clad holy men sit in contemplation waiting for seekers to climb up and listen to their pronouncements— like the template for a New Yorker cartoon. The whole truth about the caves is more practical. The theory is that, at one time, they could be reached by steps, ladders, and platforms constructed from local materials. They seem impossible to reach now because the network of infrastructure that once led to them has long since fallen away. Most of the caves were actually used to provide protection and security from the marauding war parties that frequented the area and also from the elements—snow squalls in the winter, searing sun in summer, and the unrelenting wind that tears through the valley every day of the year.

One afternoon we climbed a series of ladders to a round hole high up on the face of a vertical wall of rock. Every cloud had been chased from an ultramarine sky and the sun tormented us like a schoolyard tyrant. The mistral wind was laden with grains of sand that reflected the light like shards of glass, as if every cathedral window in France had been pulverized and sent flying skyward. The face of the cliff appeared varnished in ochre, marbled with hues of rose and plum, and streaked in the brown of a roasted nut—it might as well have been the canvas of an abstract expressionist painting. Once we ventured inside the cave, it made perfect sense. It was cool and comfortable; the best shelter you could ask for—as impregnable as the citadel of Masada and as cozy as a feather bed.

If the sky caves have a practical logic, there still exist in Mustang places of magic and mysticism. The tradition holds that the great Buddhist sage Guru Rimpoche (Padmasombhava) passed through Mustang when he traveled from India to China to spread the teachings of Buddha. Scattered throughout the area are places that he is said to have stopped to rest and meditate. I thought of George Washington in colonial America and half expected to see placards reading “Padmasambhava slept here!”

As it turns out, Guru Rimpoche could fly, so he frequented the sky caves and other locations that are even more difficult to reach, such as atop natural stone columns shaped like the hoodoos of the American west—tall, thin, and precarious.

The temple of Muktinath is another place that marks where Padmasambhava stopped to meditate, and it seemed like a better choice. As one of the world’s highest temples—3800 meters—it sits at the foot of Thorong La pass and has sweeping views of the valley below. A long stone stairway leads up to a small sanctum nestled in a sheltered grove of trees beside a spring where the wind murmurs through the branches like a whispered conversation. We washed our faces in the cool water that flows from 108 troughs shaped like the heads of bulls, the “spouts of liberation.” Muktinath is also the legendary birthplace of the Dakanis, or Sky Dancers, a type of Tantric female goddess.

The Jwala Mai Temple is situated adjacent to Muktinath and is revered for its natural cave grotto where an eternal flame, ignited from an unknown source, is fueled by natural gas that emanates from deep underground deposits and seeps out from between the rocks.

The flame is believed to have burned perpetually from time beyond time. It is small, and we had to lie down to peer into the grotto and catch a glimpse of it. The flame appears to arise from a rock next to a small pool—maybe even magically from the water itself—and in doing so unites three sacred elements: stone, water, and fire.

Jwala Mai Temple is tended by a solitary caretaker nun. This nun is young, a teenager, and she is Buddhist (again, it’s a Hindu temple). The whole temple complex is sacred to both Hindus and Buddhists so is a symbol of religious harmony where they can worship together. Sanjeev told us that in Nepal people say that no matter your place of origin, race, religion, or creed, your blood is red.

We have known Sanjeev for twenty years. He was raised Hindu but does not follow any specific tradition now. Still, he prayed in every puja room, temple or monastery we frequented. He told us “Religion is good. It’s people that make it bad.” He believes that “there is one god with different ways to find and follow him,” and described it as like a tree, where “the branches are the religions, but there is only one trunk and the soil is the same for all.”

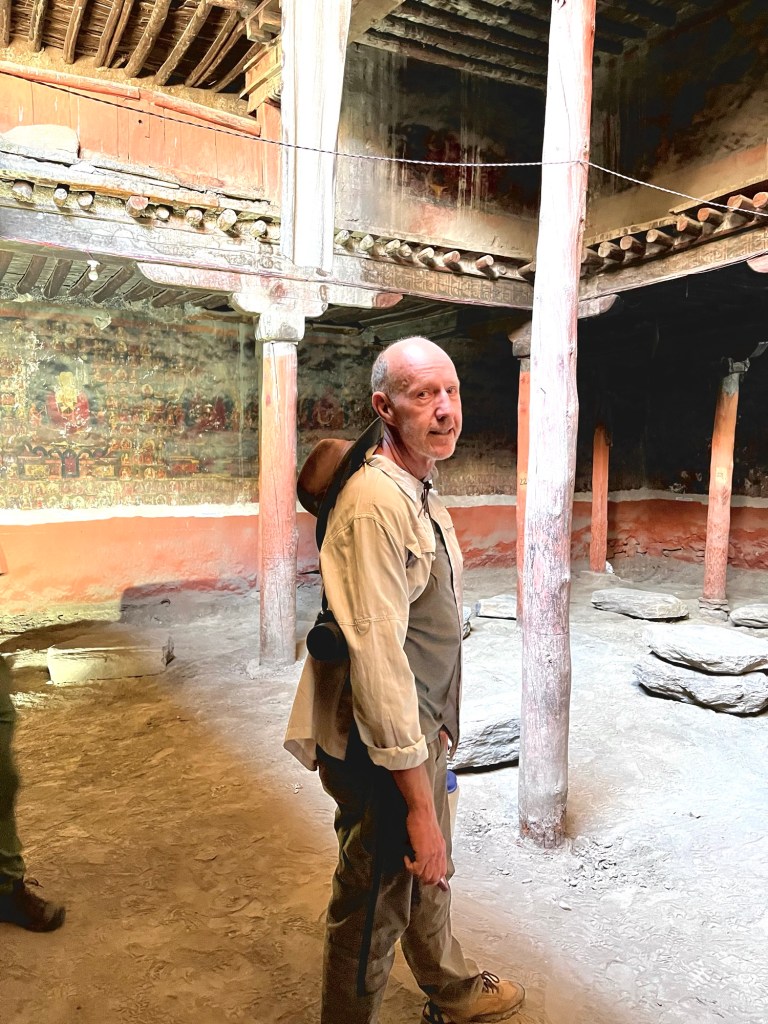

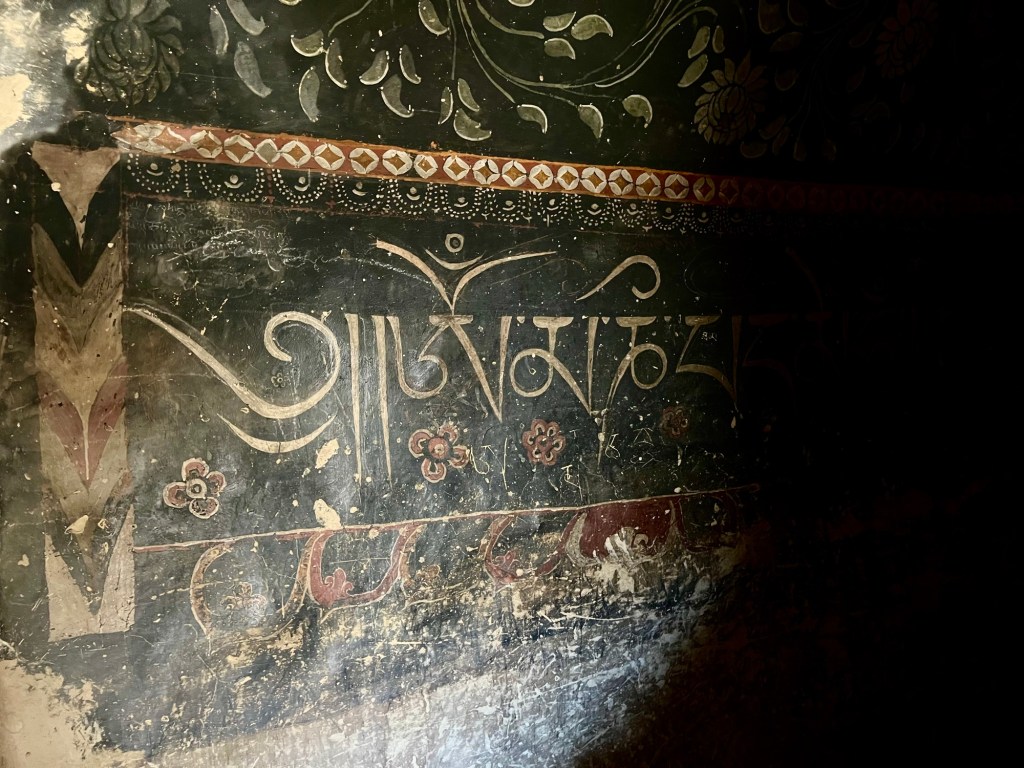

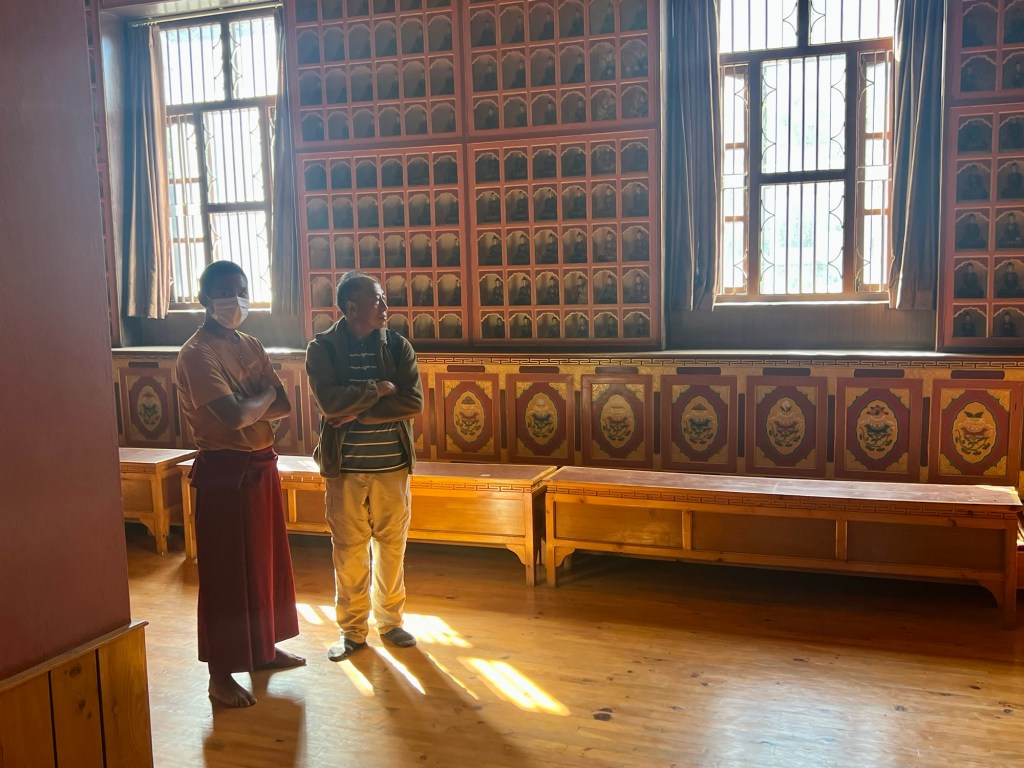

We drove from village to village, each with its own monastery (gompa) like a parish church. The serene interiors of the gompas are designed for ceremony and contemplation, so we left our shoes outside and spoke softly, if at all. The walls were crowded with intricate murals depicting mandalas, the Buddhist Wheel of Life, Bodhisattvas and the pantheon of celestial beings. They tell stories and teachings of Buddha much like medieval cathedrals in Europe use statuary and stained glass to tell about the life and ministry of Jesus. Long ago, the murals were painstakingly painted with great intricacy by generations of artisan monks using stone pigment from pulverized colorful rocks gathered from the hillsides. The finest details required a brush consisting of a single horse hair.

The inside walls of the monasteries have endured the soot of countless butter lamps over hundreds of years and have become covered by an inky patina. Some are beyond repair, while others survive and are being lovingly restored. Sanjeev’s wife Sirish Chhetri is a conservation architect and restoration specialist who has spent years leading teams who are returning some of the murals to their former splendor.

In Mustang, there are still places where one can see how it once was, how it looked a thousand years ago (or a thousand years before that); pieces of history and art that would draw crowds at the best museums around the world. The villages, caves, and monasteries are not a Disney production, created for our entertainment. They are an authentic living heritage.

Living in a monastery must have involved equal measures of adversity and enchantment. I told Caroline that we should shave our heads and spend a day at one, meditating and doing seva (selfless service or noble work).

She didn’t take me up on it. “Shaving your head? What would be the point in that? You’re halfway there already.”

We were a long way from home—we could see China from our bedroom. The traveling was difficult and we were always exhausted at the end of the day. Despite the cold and wind, we slept with the windows open because the dust and mold in our room was watering our eyes and making it hard to breathe. The tepid water in the bathroom was just warm enough to take quick splash baths, though we often chose not to. More than once Caroline informed me that, “I am not even thinking about taking a shower here. I’m sleeping with my clothes on again.”

A cow stood right outside our window, day and night. Carol leaned out before we went to bed and talked to her. She told the cow good night and to be good. It made me wonder how would a cow be bad?

It expands a person to be off the grid for a while and see what else is out there. It is good to be challenged physically and culturally. As we drove the serpentine route over yet another mountain pass, I said to Carol, “I know this is hard, but I am happy you are here with me. If you weren’t, then there would be times when I would think, ‘I wish Carol was here, she would love this.’”

Her reply, “Yes, but not all of it.”

Some places seem impervious to change, as if frozen in amber.

On first inspection, Mustang appears that way. Its geographic isolation has kept its culture, lifestyle, and heritage intact for centuries. There are still places in Mustang where you are less likely to see a person with a cellphone than one who bears nothing about them to suggest even the discovery of the wheel.

Yet change comes to the Kingdom of Lo like it must everywhere. Mud is slowly being replaced by concrete as the preferred building material and most of the guest houses have electricity, some even WiFi.

Change is creeping in, barely perceptual, like the tide.

For me and where I live, change is not that subtle—less like the tide and more like a tidal wave. True enough that everything changes, but not at the same pace it seems. My reality is different than the one in Mustang and the stark contrast has served to focus my attention on all that is changing. I have only to look around to see that things are not the same as they were few years ago, even a few days ago.

I could say the same if look inward. My body reminds me every day that I’m not bulletproof like I once thought I was, and my inner dialogue—the one I have with myself—includes more time reevaluating my place in the world and what comes next. My patients and others keep asking me when I am going to retire, and I find myself wondering the same thing. When will be the right time for me to stop doing what I have always done and do something else?

Sometimes I think that I haven’t changed enough and should have gotten better about how to live and how to be. I know that life is a work in progress, but I also know that I don’t have forever to get it right.

Here is a thought experiment to consider: Ask yourself what you would say to your 18 -year-old self. It’s not an exercise in second guessing but a method to realize what you have learned over the years. I would tell my 18-year-old self to be willing to change his mind.

It’s the young who have high standards and who insist that life be a certain way, that certain things have to happen. Yet they almost never do as we expect. I would tell my younger self that life is always arriving, so he will need to constantly adjust.

Changing your mind is not a weakness but a sign of intellectual integrity and a step toward truth. If you don’t change your mind occasionally, you’re going to be wrong a lot and be mired in ossified opinion. Wisdom is not just a matter of thinking deeply but of thinking over, rethinking, and coming up with a different solution or insight. That’s the kind of healthy change that we can embrace.

And it is always an option to have no opinion at all— just admit to yourself that you don’t know and reserve judgment until you have more information, until more evidence comes in. Something else I would tell my younger self that came to mind on my travels through Mustang is that we only know a small sliver of what is going on, so best to maintain a humble perspective about our place in the grand scheme of things.

Mustang is vast and unmastered, and it is easy to be overwhelmed with a feeling of relative smallness. I felt both humility and awe, transfixed by the inescapable sense of just how insignificant I am and how much is beyond my comprehension, freed from the delusion that the world had been sculpted to suit my ambitions and needs or the impulse to try to control everything.

In Mustang there are apricot colored cliffs and a cobalt sky, torrential rivers and tempestuous windstorms, and an exquisite stillness to the nighttime firmament where you can see a shooting star race across and think you might have heard it, too. The wildness of the land is so fiercely beautiful and starkly rugged that it calls forth and amplifies a wildness within and an awareness that you are standing in the presence of something greater than yourself, something that enables you to feel profoundly diminished and radically expanded at the same time.

Life is a flowing process with change and death a necessary part. Like a river, if it does not flow out, nothing more can flow in. To resist change is like holding your breath; if you persist, you die. The best way is to plunge in and join the dance.

Much of human effort is directed at making permanent the experiences and joys that we encounter. Yet we value some things—like an ocean wave or a kiss—because of their transient nature. Life is more like music than painting—it has movement. If a melody stops to prolong a chord beyond its time, the fluidity is lost and so is the meaning and purpose.

As we get closer to the end, we have thoughts of our lives, how the narrative played out and stacked up against the hopes and dreams we had chased in our youth. What would my 18-year-old self say to me? Would I disappoint him?

We should not regret the past, just learn from it and move on. And hold on to the idea that change is opportunity and the possibility that we can always reinvent ourself better than we had been before.