Everyone knows the first rule of Fight Club. As it turns out, there is a similar first rule of the Camino de Santiago.

It is this: Pilgrims don’t ask other pilgrims the reason they are walking.

Some of the reasons we do things are private, and some things we do without a conscious reason. Nothing wrong with that. The unexamined life may not be worth living, but an over-examined life can be tiresome.

Caroline and I walked the Way of Saint James together, she for her reasons and me for mine, but it’s not something we needed to talk about.

For many pilgrims, the Camino is a spiritual quest, or they hope for it to be. Even that reason doesn’t say very much or tell the real story. An individual’s spiritual journey is as unique as their fingerprints. I watched a movie where one character said, “I’m not a religious man,” and his friend said, “Religion has nothing to do with it.”

I think it’s that way for most people walking the Camino. The motivation to walk runs deep, but religion is not the biggest part of it. And I think that a true spiritual journey is something you take with a part of you other than your feet.

I do know how it started for me. It started with a book.

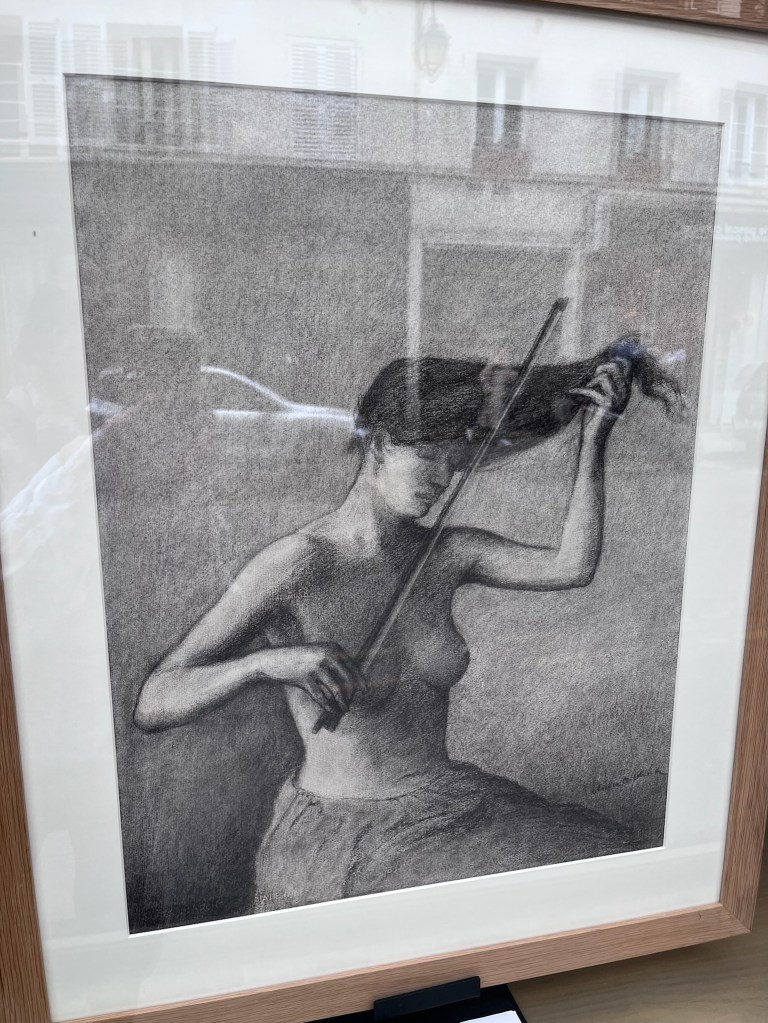

Like the music we listen to and movies we watch when we are young, the books we read in our youth are formative to who we become. Song lyrics, poems, and stories give voice to what we feel but don’t know how to say. We read a book and want to be in it or bring a part of into ourselves. The creations and characters we encounter over the years form a personal cannon, and we become the curator of our life.

Environmentalists and certain types of nonconformists carry with them a copy of Walden as if it is their Bible, J.R.R. Tolkien has left his indelible mark on untold numbers who would say that after reading Lord of the Rings they were never the same, and just the thought of Ol’ Yeller brings a tear to the eye of every dog lover.

On the other hand, some of the songs and the books that come to us early in life don’t hold up as we grow older. I loved Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance the first two times I read it, and I credit that book with opening new worlds to me, but I read it again a few years ago and didn’t feel the same magic. I read Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged when I was college age –the same stage of life that most people read her–and thought she was really onto something. Now I think, not so much.

The Pilgrimage, by Paulo Coelho is another book from my personal canon. Coelho is a well known author now, but he wasn’t back when I read his first and most popular book, The Alchemist. I liked that one, so I read his second book about a man on a spiritual quest on the medieval pilgrimage route across northern Spain. Spiritual, yes, but in the broadest sense. The book is more about finding himself than finding God.

Before reading that book, I had never heard of the Camino de Santiago de Compostela and I had never entertained the notion of going on a quest. Yet I’ve always liked to travel, and they say that when telling a story, any journey represents a quest; every journeyer, whether they know it our not, is really on a quest, and the objective is not what they think they are seeking. What the hero is actually seeking is not a holy grail or a pot of gold. The prize and true destination is self -knowledge.

Which was a something I needed a lot more of back when I first read The Pilgrimage: self-knowledge. I was not even self-aware enough to know I was not self-aware. But I must have known something was missing, because the book drew me in and has been in the back of my mind ever since.

So that’s how I found myself walking across northern Spain.

The story of the Camino de Santiago de Compostela is a tale told from equal parts history and legend.

James and his brother John, sons of Zebedee, were fisherman on the Sea of Galilee and two of the first to follow Jesus. Just before the crucifixion, Jesus told all his apostles to scatter across the known world and spread the word. Peter ended up in Rome, Thomas in India, and John the Evangelist in Asia Minor. James washed ashore on the Iberian Peninsula. He wandered through Galicia, in what is now northwest Spain, but eventually returned to the Holy Land where he was beheaded by Herod Agrippa, the first of the apostles to be martyred.

Friends slipped his body out of Jerusalem and put it on a ship made of stone with no sails or sailors. The boat was miraculously guided by angels across the Mediterranean, through the Straits of Gibraltar, to the Iberian Coast. Some of James’ disciples back in Galicia, who were somehow alerted of his arrival, took his body off the boat and placed it in a small tomb on a mountainside.

There is no further word of Saint James for eight hundred years, and during that time the area was slowly Christianized.

In 813 a Christian shepherd, a hermit named Pelagius, saw lights shining from a cave. He went there and dug until he found bones and a parchment, which he took to the local bishop who authenticated the bones as those of James and two of his disciples. One version of the legend is that Pelagius and the bishop were led to the location by a star, hence the name Compostela, (Latin: Campus Stellae, “Field of the Star.”)

When the Spanish king learned of the discovery, he had a small chapel built to mark the spot and hold the relics, and, as more people came to visit, the town around the hill grew in size.

The pilgrimage that started as a trickle would swell and the city of Santiago de Compostela grew to accommodate the numbers. A larger cathedral was commissioned to replace the chapel, and in 1075 ground was broken on the Romanesque and Baroque masterpiece that now serves as the final destination for the multitudes who walk the Camino.

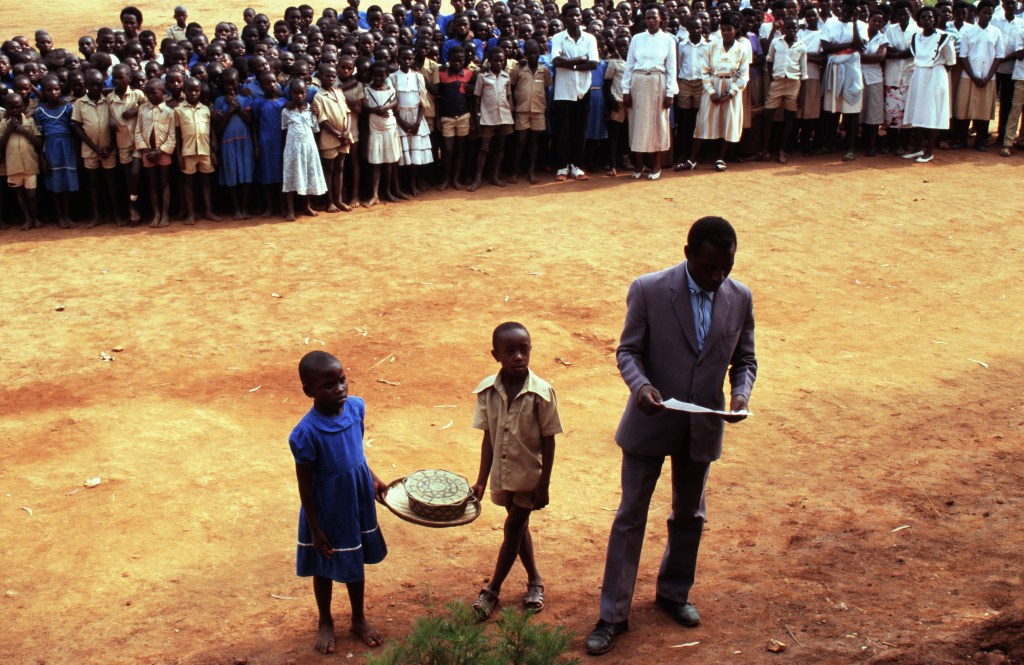

Saint James –Sanctus Iacobus (Latin), Sant Iago (Old Spanish), Santiago (Modern Spanish)-became the patron of Spain. In medieval times, the Way of Saint James was traveled as a way to salvation or to pay a penance, and throughout the Middle Ages more and more people took part. The numbers dropped during the Renaissance and Enlightenment, but the line of pilgrims has remained unbroken for centuries, and there has been a modern resurgence in the Camino as a source of cultural exchange and understanding among people.

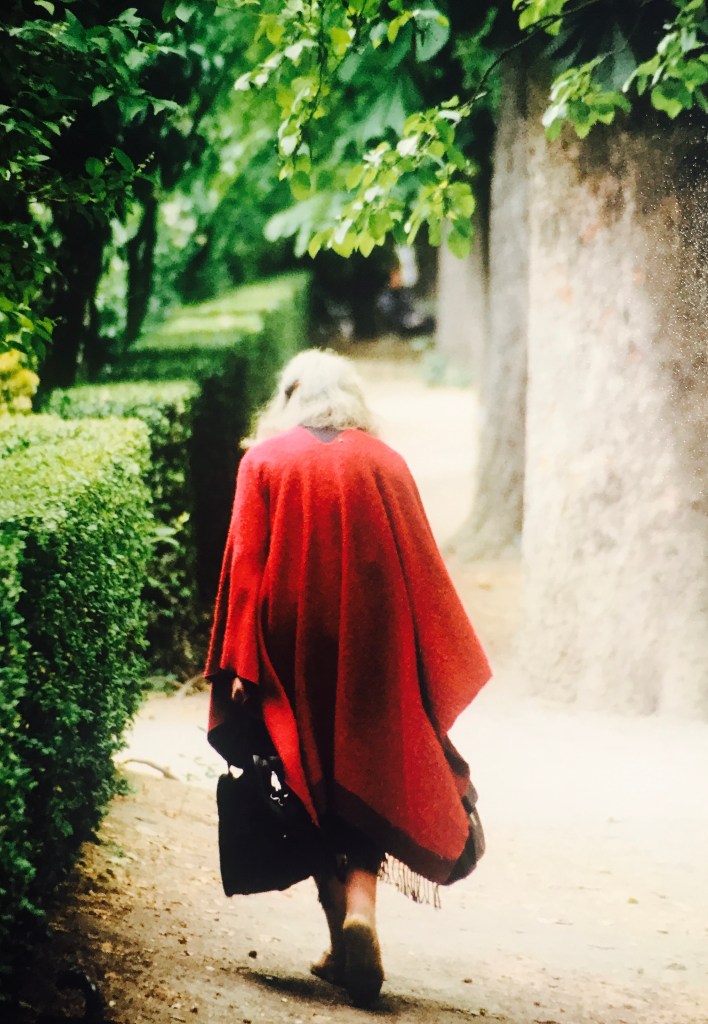

For many, the Camino remains a sacred journey, symbolizing a profound act of devotion while enduring physical trials, with the hope of divine grace. For everyone it is a means to be a part of something greater than themselves. We were following in the footsteps of people from ages ago and walking in the shadow of kindred spirits from all over the globe.

A journey’s beginning is wherever you start from, so a pilgrimage actually starts at the individual pilgrim’s front door. That means there are as many Caminos as there are pilgrims. And yet, because the journey has always been long and perilous and there is safety in numbers, people began to walk together. A pilgrimage community was created and routes were established with designated starting points, where people gathered from all points to start the walk across Spain.

In the center of Paris, mere steps from the River Seine, there stands the tower remnant of a former church that was demolished during the French Revolution. Tour St Jacques is one of the traditional starting points of the Camino (French: Chemin de Compostelle), and it is where Caroline and I began ours. It is where we saw our first scallop shell.

From the earliest days of the Santiago Pilgrimage, its symbol has been the scallop shell. James was a fisherman, of course, and shells have always been found along the shore of Galicia. And there are legends about James encountering a mystical horse (some say a knight) who, emerging from the sea, was covered with shells.

As keys make us think of Saint Peter, so the scallop shell signals Saint James. When you walk the Camino, you see the shell everywhere: on trail markers, clothing, street signs, and the placards of the hostels where pilgrims sleep. A scallop shell hanging on the back of your rucksack identifies you as a member of the special fraternity of pilgrims to Santiago. Wherever you are from, and for whatever reasons motivate you to walk west, you are entitled to wear the the shell as the universal insignia of the Santiago Pilgrim.

Rue Saint Jacques leads away from Tour Saint Jacques. Caroline and I followed it south, past the Sorbonne and Pantheon, before we circled back to visit the unveiling of post-fire Notre Dame Cathedral.

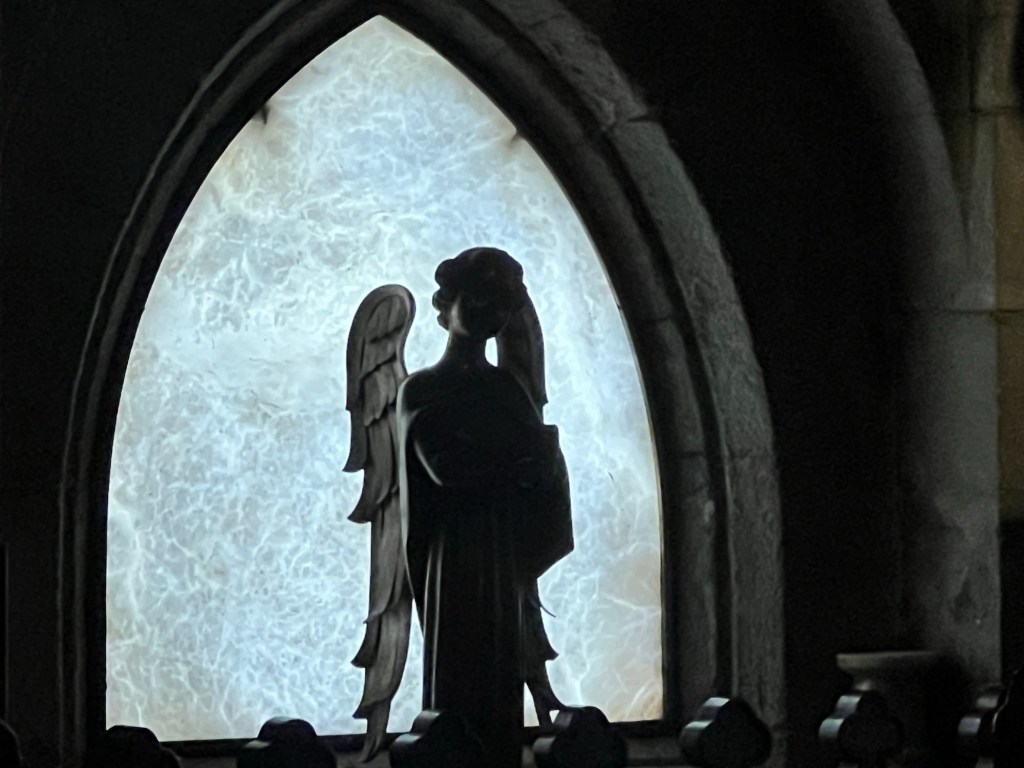

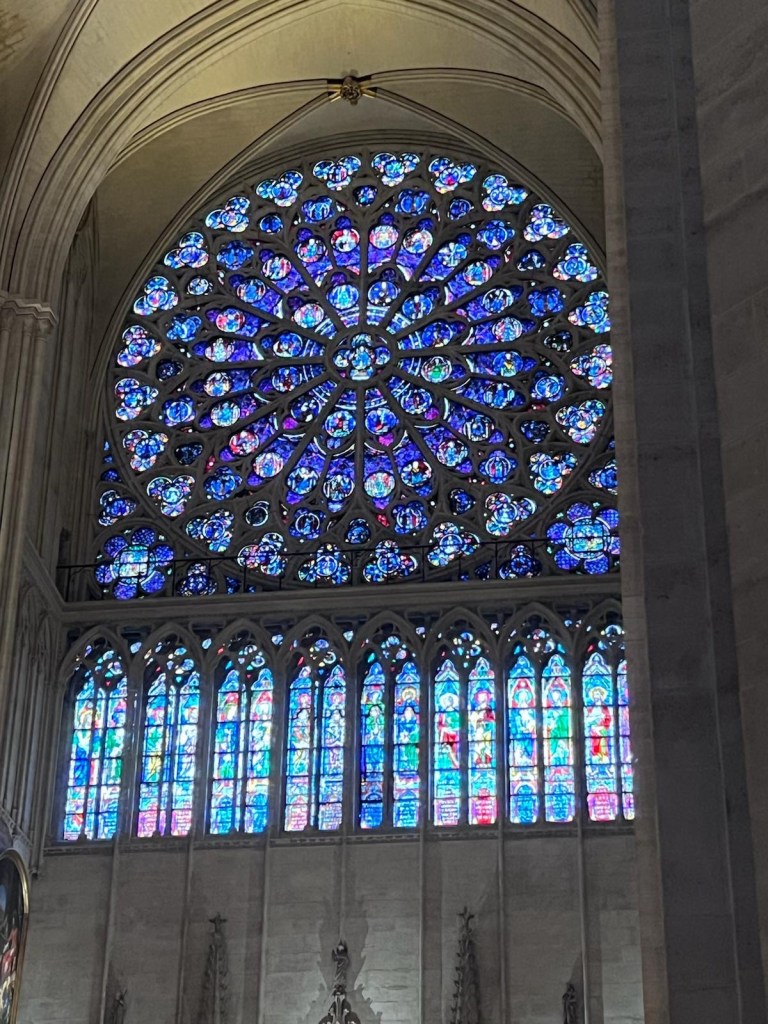

It’s an aside from my story here about the Camino, but I want to report that Notre Dame is back. It is a wondrous site. Anyone who stood inside its nave before the fire and returns now is awestruck, they have done a magnificent job of putting it back together. It’s the same place as before, but now wearing bright and beautiful garments, like Cinderella before and after the fairy godmother. The cathedral was brimming with people, but I didn’t mind the crowds because every person looked so happy, smiles on their faces as they gazed upwards.

We didn’t walk the rest of the way through France but rode the train to the starting point of Camino Frances in the town of Saint Jean-Pied-de-Port, which lies just before an arduous mountain crossing to the village of Roncesvalles in Spain.

The most populous route is Camino Frances, which starts on the French side of the Pyrenees mountain range and then traverses across northern Spain. We followed the Frances to Pamplona and then moved to Camino Norte, along the coast of the Bay of Biscayne. There also are two Portuguese routes that approach Santiago from the south and other less traveled routes in Spain. The pilgrimage routes are like tributaries of a great stream headed towards Santiago. A map of them resembles the lines of the scallop shell resting on its side.

Pilgrims traverse diverse landscapes and historic villages. They step into silvery sunrises and stain glass chapels in faded afternoon light. We walked down bustling urban sidewalks and through cobbled village squares, over treeless, wind-swept mountain passes and into misty, Brontë-ish moors, through verdant forests and glens cleaved by babbling brooks, following shadowed footpaths so picturesque they could have been leading us to the Shire.

We encountered animals enough to populate a petting zoo. There were cows with long eyelashes who stared as we walked by and donkeys who paid us no mind at all, waddling ducks and gaggles of geese, draft horses making muddy footprints the size of dinner plates, dogs both friendly and menacing, and farm cats asking for handouts as we picnicked.

This was Basque Country, so we were never far from a flock of sheep, and a memory welled up in me. I used to think it would be a fine thing to be a shepherd. It’s possible that I would have changed my mind if I had ever actually been one (it might be harder than it looks), but shepherd was one answer to the question we ask ourselves after a certain age- what might I have done with my life if not this; what choice of vocation, if not the one I am in now?

Shepherd was at the top of my list until I went to a sound-therapy session in Bali and learned there is such a thing as a Gong Master. I thought that sounded even better.

I drifted back to the idea of shepherd late one afternoon as we wound our way over a high pass in the Pyrenees. As the weather and sun painted the horizon, I watched sheep traverse the western gradient of a gently beveled hill. I saw their shadows lengthen in the slanted light and heard the tinkle and clang of the bells around their necks. It sounded like a wandering wind chime. I imagined myself there, like a character in a Thomas Hardy novel, trailing behind my flock as my loyal dog darted back and forth, guiding the sheep over the next ridge. I think I would have liked that.

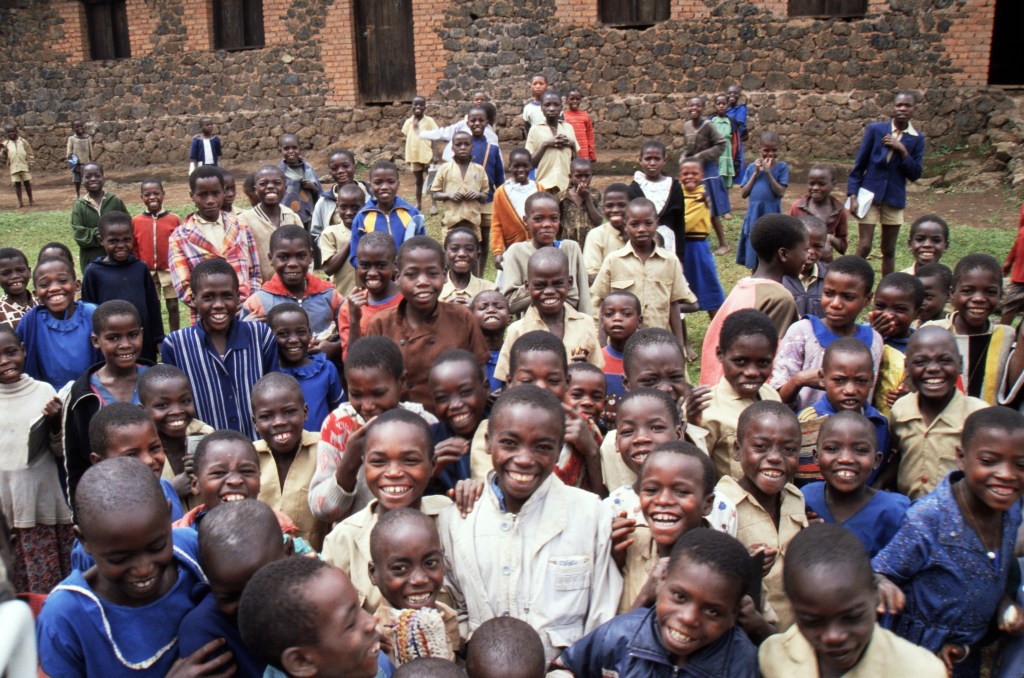

The bucolic scenery was appealing, but even when we had fully given ourselves over to the landscape, it was the people we shared it with that made our trek a pilgrimage. The most famous story about a pilgrimage–the one on the road to Canterbury–is really a story collection about a community, not one person, and it is the same on the road to Santiago. Humans have always been up for a pilgrimage, whether to Compostela or Cooperstown, and every pilgrim has their story.

We walked with people from Austria to Australia, and from the entire range of ages and ethnicities. For some, it was their first time, while others had returned to the Camino many times. We spent an hour climbing up a steep hill alongside a young couple from Canada. Caroline and I opened the conversation by apologizing to them on behalf of our country. They smiled and replied that while governments and politicians can sometimes be a problem, they love the US and Americans.

Our pattern was that we would fall in with someone, become fast friends, then part ways. That is the way of the Camino–connections are made, but you don’t expect to keep them. We smiled at the thought of how many times we said a heartfelt farewell, only to meet up again somewhere down the trail with the people we just said goodbye to.

Out of all the pilgrims we walked beside, the one we will hold onto is Abe Sanoja.

Abe was an executive at Hewlett Packard until he left that company to create a different one, and then he sold that one a few years ago. He was a successful businessman but left it all behind because he wanted something different for the next part of his life.

On the Camino, Abe did not inspire visions of an ambitious executive. He was more like one of the faerie folk–Puckish like a tall leprechaun. He had the required beard, impish grin, and twinkle in his eye, a Will-O-The Wisp in all but the little green tights. Hand him a pipe and he could blow smoke rings. Caroline said he was the Camino “sprite” in the way he would materialize out of thin air and then disappear again, and I agreed that magic and serendipity seemed to follow him like a shadow.

We ate dinner with Abe early on the route. We enjoyed each others company but, as it goes, we said our goodbyes in the morning and went our own way.

The next day, Caroline and I entered a small village square after walking all morning in the rain. We were wet and tired, and as we climbed the steps toward the only cafe that was open, there sat Abe under an umbrella with two chairs waiting for us, a plate full of Spanish olives on the table, coffee and empanadas on the way.

Abe is blind in one eye because when he was a boy he couldn’t resist looking directly at a solar eclipse. He has compensated by honing his powers of observation, and now he can easily identify people by their walk, even from afar. He spotted Caroline approaching well before we saw him.

Abe is now a full time pilgrim. He treks all over the world but mostly on Caminos. We were with him in October and he had not been home since February. I don’t know if he could put a number to the distance he has walked, but it would be enormous, like if Forrest Gump kept count of his steps. Abe is indomitable, endlessly curious and eager to see the territory ahead, whatever is waiting for him. I wondered if he was born too late and would have been happier in the Age of Exploration alongside some arctic explorer or standing at the helm of a majestic tall ship.

I tried to imagine other enchanted beings Abe might personify. He imparts mirth but also wisdom, so maybe a wizard. Or a magi, since he travels a lot. Or some character that embodies the idealism and thirst for adventure that is embodied by the Camino. He’s in Spain, so I’ll go with the Man of La Mancha, dreaming the impossible dream.

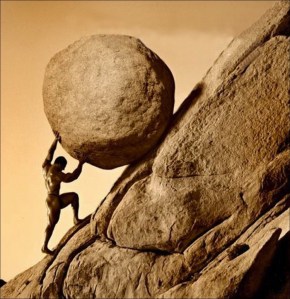

With his powers of observation and more time walking Caminos than anyone, Abe attests that the journey itself is the teacher and that walking the Camino instills patience, humility, generosity, perseverance and courage–instills it, but also reveals it; because you need those qualities to even get started. He declares that when amidst the serenity of wind, ocean, and sky, you learn to walk humbly, listen before deciding, respect and protect the freedom of others (even if you disagree with them), and see life as it really is, without noise or excuses. Every step matters, and if the path is wrong, you stop, reflect, and change direction. Sometimes, being lost is the first step in finding yourself.

Step by step (paso a paso) is Abe’s first principle. It’s the way to get anything done. Just take the next step.

And therein lies another rule of the Camino. Don’t complain. It is a rule both unwritten and unconscious, yet it is innate in all pilgrims. They just don’t.

Caroline and I never heard a complaint from others and we learned to swallow our own. If we said something to Abe about a particularly difficult stage, his response was always a shrug while saying, “Juat keep going.”

Not to say we didn’t come close to complaining at times. Like when Caroline and I were limping though the remains of a day that proved to be harder and longer than I had predicted. To Caroline I said, “It’s always farther than you think.” And she replied, “Don’t EVER make me look at another map!”

In the central square of Pamplona we stood in a protest rally that followed a long march through the city. We listened to an impassioned speech from a young woman who exclaimed to the marchers, “I know you have had a very long day today!” To which Caroline muttered, “You haven’t had as long of a day as I have.”

The overarching rule of the Camino might be that you don’t criticize how other pilgrims walk their Camino.

For some it is a solitary, deeply contemplative event, and you respect their desire for space and quiet. For others it’s an entirely social affair. They travel in groups and don’t stop talking. For some, it’s all about collecting their Credential (certificate of completion) at the end, and there are others, like Abe, who don’t care at all about the paperwork. Some break it up into half stages, and others (Abe, again) add on extra miles. But there is no right or wrong way to do a pilgrimage. About the walking to Santiago, pilgrims don’t ask why, and they don’t judge how.

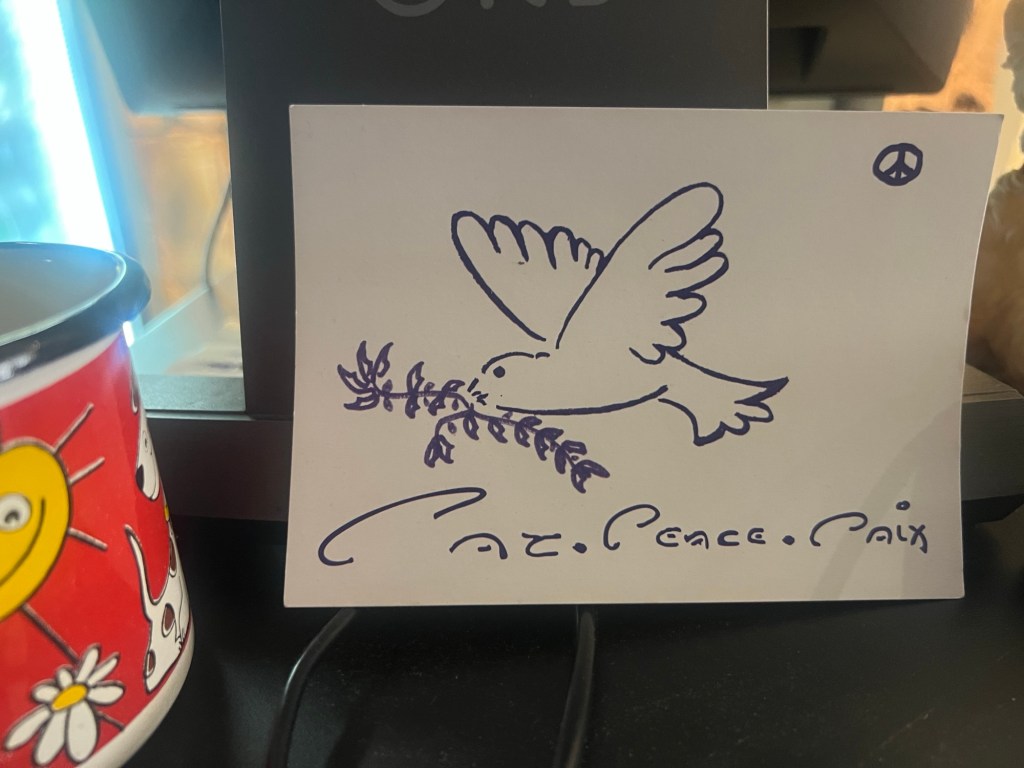

Dogmas should be held lightly and rules approached with caution. Everyone shares water, stories, and advice, and it’s best to get along. It’s a peaceable kingdom. A place where you recalibrate what matters and what makes a good day. You reside within a mingling of solitude and community, to the wider world simultaneously separate and connected–the way an island must feel about water.

Many pilgrims reach Santiago and wonder what happened to the spiritual epiphany they were expecting. I don’t think walking the Camino works that way.

“It is solved by walking” is a proverb attributed to St Augustine (or some claim the Greeks before him). And Hippocrates famously prescribed, “If you are in a bad mood, go for a walk. If you are still in a bad mood, go for another walk.”

Joseph Campbell, the acknowledged authority on how humankind has searched for meaning though mythology and religion, in the end said, “I don’t think people are searching for the meaning of life as much as they are the experience of being alive.”

For me, I think it is something like that. I didn’t go in expecting an epiphany. I did have the experience of feeling alive.

The Camino is a physical challenge, an exercise in introspection, and a crucible of companionship and connection. I think the best lessons of the Camino speak gently and gradually, similar to any enduring life lessons.

Here are some lessons from the Camino that apply just as well to life outside of it:

- Don’t complain. Just keep going.

- Keep a positive attitude. Believe that the world tries to land right side up.

- If something doesn’t take hard work to get, it’s probably not worth having

- The world does not stop for me. It goes on with or without me

- Curiosity will be rewarded

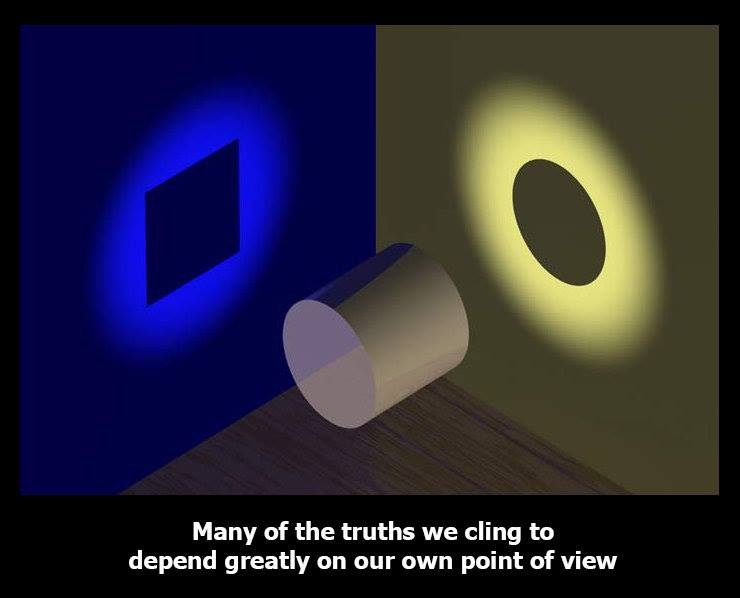

- Don’t criticize or judge the way others do their Camino walk or their walk of life. None of us know the truth of the other’s journey.

- Your goodbyes should be written in water. Chances are, you will see each other again.

- Notice magic and serendipity when it happens. That’s what can make a walk a pilgrimage, your story a quest for self discovery, and your life a hero’s journey.

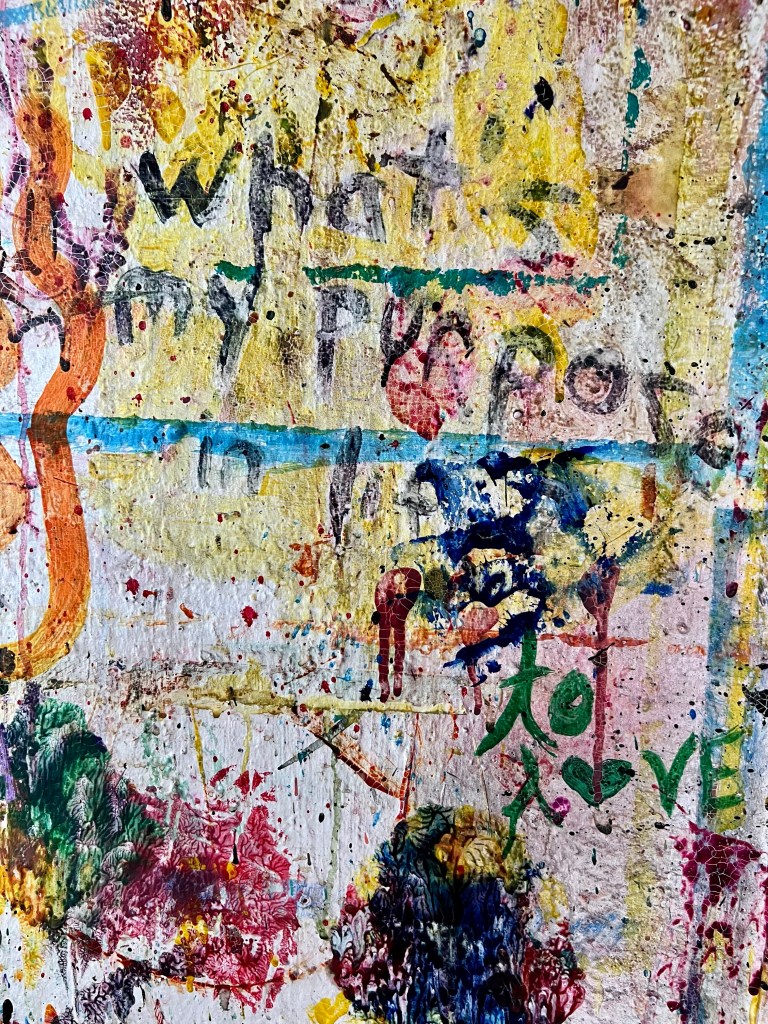

What is my reason to walk the Camino de Santiago?

I can offer this last item about Abe–he invited Caroline and me to come stay at his house in Seattle.

Nice of him, but when he said that my first thought was–Really? You barely know me.

But he knew me enough.

For me, that he could think that and say it is reason enough to want to be a pilgrim.